As cybersecurity threats put sovereignty at risk, digital standardisation is getting caught in the maelstrom of geopolitics. The 5G debate – the “geopolitical moment” in the digital transition – showed that most governments largely ignored standardisation at their peril. What is needed is a revised governance of standardisation that is fit for global collaboration and that respects sovereignty.

The Financial Times recently reported on China’s domination in the setting of standards for facial recognition and surveillance at the International Telecommunications Union, a United Nations body. Similar observations have been made about the increasing influence of Chinese companies like Huawei in 3GPP, the consortium that establishes many of the standards surrounding 5G and related 5G security. This comes at a time of deep geopolitical controversy for 5G.

The contention is that it is a deliberate strategy of the Chinese government to set the rules of the game in new areas of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) and to break with past standards, which have largely been determined by the United States and Europe. This strategy, it is believed, dovetails with massive nationalistic procurement and aggressive international investment.

But the future of the digital transition shouldn’t only be framed in terms of a conflict between China and the US. Above all, there is a clash of two major forces in international politics: globalisation and sovereignisation. The latter can be understood as the narrow view that sovereignty is fundamentally defined by an ever-lasting power struggle and a lack of trust between states. The “geopolitical moment” in the digital transition is the 5G debate. Indeed, ICT standardisation will become the next geopolitical battleground, driven by concerns about sovereignty: a loss of competitiveness, an insertion of vulnerabilities through the development of ICT standards, the systematic theft of intellectual property, and state-capture of standardisation as part of an expansionist international agenda.

What the world needs now is a better understanding of how standards work, why they matter for global progress, and how to prevent standards from being instrumentalised in the pursuit of narrow interests.

The Beauty of Standards

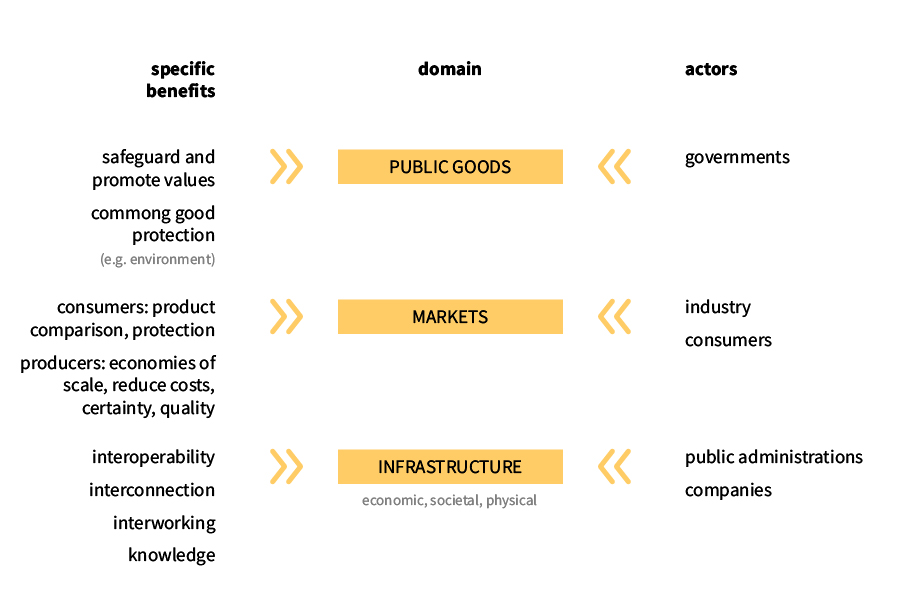

Standardisation creates widely agreed-upon rules, guidelines, and specifications. These standards enable the economies of scale that bring economic benefits like reduced manufacturing costs, lower prices, and increased consumer choice.They can bring about the enhanced protection of fundamental values(such as privacy) and common goods (such as the environment). Standards make possible interconnected infrastructures that can span the globe and are the basis for economic and societal activities across the world. Standardised access to the Internet and mobile communications is a key enabler for the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals of inclusion, empowerment, equality, and global partnership.

To be fair, the development of standards may seem boring. It involves lengthy discussions, often with hundreds of experts weighing in on detailed technical matters for organizations like ISO (general), 3GPP (5G telecoms), and oneM2M (Internet of Things).But standards play a critical role in our economies and societies.Studies have shown that standards contribute to German GDP growth by around 25 percent and to labour productivity growth in the Nordic countries by nearly 40 percent. Some standards have been a runaway success. Take the GSM standard for 2G, a (by now ancient) precursor to 5G. Standards can also be closely linked to legislation. In the EU, for example, consumer protection laws refer to the conformity with standards for product safety. Goods that make the cut bear the CE certification mark.

In the digital realm, the optimal standardisation would be global. Most digital services are relevant around the world, and they function thanks to standards-based interoperability. Economies of scale, in fact, are best achieved in such global value chains. Tackling problems of a truly global dimension, like climate change, cannot happen effectively without global ICT, which can assist with global emissions trading, for example.

Yet all of these laudable goals are threatened as ICT standards risk being torn apart by geopolitical tensions.

The Blast of Change

The link between geopolitics and standards is not new. Regional and national assertiveness on an international level was visible in Japan in 1877 with that country’s reasons to join the Universal Postal Union, and in the creation of a European voting bloc in the 1990s to influence mobile telecommunications standards. Over time, the World Trade Organisation became a battleground for states to call each other out for using standards as a barrier to trade. Emerging economies often lament that global standardisation platforms are the playground of wealthier states – ones that have the money and the manpower to participate.

But the current chapter in the geopolitics of standardisation is different. The ongoing digital transition profoundly affects the sovereignty of states. And it does so across all sectors of the economy and all layers of society and political systems.

First, “digital” is now pervasive and indispensable, transformative and disruptive – all at the same time. The original Internet was globally distributed and decentralised, but that didn’t prevent the monopolisation of power, thus distorting relations between individual states as well as between private and public actors. Also, most ICT isn’t secure-by-design, thereby leaving economy, society, and democracy vulnerable to state-sponsored cyber intrusions and to cybercrime. Disruptive transformation, non-secure ICT and international tensions all combine to put sovereignty at risk. It’s therefore unsurprising that states have responded by trying to assert more control over the direction of the digital transition. Governments seek strategic autonomy in the digital world or in other words, technological sovereignty. One element of this is the control of ICT standardisation.

Second, governments have suddenly realised that they left control over certain parts of critical digital infrastructure in the hands of the private sector. This wouldn’t be a problem if the private sector delivered what governments wanted in terms of security: isolation of affected parts of essential infrastructure or switch-over to a backup facility in case of a cyber crisis; affordable market-based technology that can still be used in sensitive environments; and no single vendor lock-in. But either this isn’t the case or governments simply don’t feel reassured. The best illustration of this is 5G. As French President Emmanuel Macron said during a recent interview about 5G security: “[s]overeign decisions and choices were de facto delegated to telecoms operators”.

Third, as argued in the report by the expert panel on standardisation in the digital age chaired by Carl Bildt, standards should no longer be delegated or dealt with in technical forums only. Instead, they should be seen as a strategic means for EU competitiveness, quality of life, and indeed strategic autonomy and sovereignty in the EU. The taskforce found that standardisation should be revalued as a strategic question and that standardisation policy should not only be consistent and integrated with other policy measures but should also work to support overall strategic objectives. Its message was clear: Standards should be revalued in the context of international politics.

Where To Go From Here?

It may seem like there are no good options. True, the push to get standardisation processes to better reflect geopolitical realities is a serious impediment to global collaboration and the establishment of global standards. Yet this is exactly what is needed to promote global peace and security and to drive economic growth and social welfare.

Political “hawks” may well view geopolitical competition as a natural outgrowth of power struggles and a fundamental lack of trust. They could interpret any push for global cybersecurity standardisation as a power tactic, a means for one’s own government to exert control. Less conservative “doves”, on the other hand, would likely accept that certain cybersecurity issues should be dealt with globally, while at the same time emphasising the value of sovereignty. One example would be the management of the public core of the Internet. But they would have to be convinced that this could be achieved without a loss of sovereignty, and they would likely insist that governments define the parameters of global standardisation collaboration in a way that it delivers global standards without undermining sovereignty.

There are also those who reject state-centricity when it comes to global standardisation. These are mostly actors from academia, civil society, and industry. They believe that the first step for digital standardisation should be to create global common goods, i.e. global digital standards that deliver the benefits outlined in Fig. 1 to everyone.

So, what can be done? How can the risk of a splintering in the digital world be minimized? How can this challenge be addressed in a constructive way?

First, the companies and technology experts who are driving the standardisation processes today need to be proactive about engaging with governments and addressing their concerns. The days when engineers, techies, and policymakers all lived in separate bubbles are over. If governments – at best – are kept at arm’s length or – worse – are kept out, it’s unlikely that global 6G or a worldwide, interoperable IoT can ever become a reality. By the same token, this also means that policymakers need to invest more time and resources in standardisation.

Second, sooner or later these questions must be discussed at the UN. The cyber confidence building measures agreed upon by the governmental experts, for instance, will never be effective unless they’re supported by standards like the standardised information exchange on vulnerabilities or the ICT security certification of critical infrastructures. This is not yet being championed – even though EU countries should have a significant interest in it.

Third, stakeholders who don’t frame cybersecurity standardisation as geopolitically contestable but rather as grounds for global collaboration should be given a full role. The chief interest of these stakeholders is the proper operation and continuity of their core business areas – such as health care, manufacturing, or the automotive sector – or indeed of the global Internet itself. They are not concerned with hard-core national security. They can credibly promote open source, open standards, standardised cybersecurity skills, and globally recognised security standards such as ISO 27000.

Fourth, there is as much tactical behaviour as there is strategic intent in standardisation. Diplomats will be familiar with such behaviour. This includes using process and procedure for strategic or tactical intent or tying in other diplomatic agendas (e.g. linking cybersecurity with trade and international crime negotiations or with arms control). And while there is more information available about companies’ strategic intent and tactical behaviour in global digital standardisation, such as 3GPP, less is known about that of states.

As such, actions that could be taken at the EU level include:

- Encouraging and supporting policymakers and governments to engage in global standardisation. (The European Commission’s 5G security toolbox from January 2020 is a positive step in that direction.)

- Providing political framing and other support to help global digital standardisation complement UN cybersecurity negotiations (possibly by the European External Action Service and the European Commission in the forthcoming Security Union Strategy).

- Supporting industry, civil society, and academic stakeholders in order to promote a global and inclusive approach to standardisation (using Horizon Europe, the Digital Europe Programme and the EU Cybersecurity Act).

- Tapping into the extensive experience of EU diplomats and negotiators to build a comprehensive understanding of the new geopolitics in digital standardisation.

Such actions would empower European actors to lead in a revised governance of standardisation that is fit for both global collaboration and that respects sovereignty.

This commentary is also available in French. Credits to ‘Le Grand Continent‘ for the French translation.