Russia committed a grave violation of international law when it invaded Ukraine one year ago. Russia and Ukraine are at war, but are they also at cyber war? We have seamlessly passed the much-debated Article 51 UNC threshold and moved into a cyber warzone, where shelling of Ukrainian towns and villages is accompanied by cyberattacks on its allies’ critical infrastructure. How does this impact the application of international law in cyberspace? Here, a recap of the first year of the Ukrainian cyber war and how international law is being applied.

Russian aggression in Ukraine

We are one year into a two-week invasion. On 24 February 2022, Russia attacked Ukraine under the guise of a ‘special military operation’ that was really a failed attempt to replace Ukrainian democratic institutions with a puppet government operated from the Kremlin. On 20 February 2023, US President Biden made a top-secret surprise visit to Ukraine to express his moral and military support for the people of Ukraine and to announce a $500 million aid package. The President also announced further supply of military hardware and ammunition, as well as another packet of sanctions targeting Moscow.

European states and international lawyers agree that the military invasion of Ukrainian territory by Russian troops is the first act of armed aggression in Europe since the adoption of the United Nations Charter and – in turn – appropriate measures apply. One could argue that the actual invasion happened back in 2014, with the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation, when ‘little green men’ affiliated with local paramilitaries took over the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol, physically invading the territory of the independent Ukrainian state. The Russian invasion has been continuously accompanied by enhanced cyberattacks and advanced cyber operations. The scale, scope and range of these attacks has advanced to an unprecedented scale in the current, full armed conflict. Below, we examine the cybersecurity aspect of the past year of war in Ukraine from an international law perspective.

Is this cyber war?

Yes, it is. This is cyber war at its finest. We have passed the UNC Article 51 armed attack in cyberspace threshold: the enhanced cyberattacks aimed at Ukrainian critical infrastructure add to the kinetic effect of traditional weapons. Ever since, Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine has been accompanied by cyberattacks and advanced cyber operations. Advanced persistent threat (APT) and DDoS attacks have long been a part of the contemporary military arsenal and had potential to be considered a decisive element of an armed attack in cyberspace. Yet only following the invasion of Ukraine, in the context of the most bloodstained conflict in contemporary European history, have individual states and the European Union recognised cyberattacks as constituting an armed attack and attributed them to a state.

Would the assessment of Russian APTs after 24 February be different, were they not accompanying military troops in Ukrainian territory killing its people? Indeed: if these cyberattacks were not complementing and enabling military action on the ground, it’s likely states, international organisations and civil society actors would still be refraining from calling them out as acts of cyber war. Similar scenarios in the same geopolitical setting unfolded, for example, in the icy winter of 2015 with the Ukraine power grid hack and a year later with the 2016 Kyiv cyberattack, but no public attributions to a state followed nor were international proceedings initiated.

Measuring cyber war

What’s different about these cyber operations, and how do they vary from the 2015 or 2016 operations? What changed for states and academics to be able to declare a state of cyber war in Ukraine? Have attacks never been deployed at this scale or using this mode of operation or these advanced technologies before? How have we so seamlessly passed the much-debated armed attack threshold in cyberspace? These questions are fundamental to an international law assessment of the Ukrainian (cyber) war.

There are no easy answers to these questions. International lawyers and courts alike have struggled to define ‘an armed attack’, a definition that fundamental to the most significant armed self-defence exception in the United Nations Charter. Following Roscini’s distinction, the cyber operations in Ukraine fall within the second case named in the Common Article 2 of the Geneva Conventions and customary international humanitarian law. They can be qualified as cyber operations which ‘occur in the context of an already existing international armed conflict and have a nexus with it’. Life has offered the much-needed context and explanation for Rule 20 of the Tallinn Manual allowing for ‘cyber operations executed in the context of an armed conflict’ to be ‘subject to the law of armed conflict’, even if they individually might not amount to armed force. The silver lining, if any, for the international law context of the war in Ukraine is clear: we are witnessing a cyber war and this is the time to test all the theories we’ve developed on cyber war thus far, including those on the necessity and proportionality of countermeasures to address it.

Proportionate and necessary countermeasures in the Ukrainian cyber war?

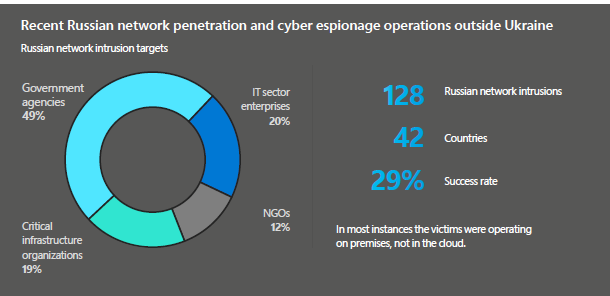

As thoroughly explained by Delerue, the necessity of countermeasures implies the need to determine whether a specific measure used for self-defence is necessary to achieve a legitimate purpose and has no alternative. Moreover, a countermeasure must be aimed at repelling the attack. When a countermeasure is determined to be necessary, it must also be proportionate. This criterion implies that the more severe the attack, the tougher the countermeasure. This is interesting, given that the scale of cyberattacks in Ukraine is unprecedented. Microsoft has flagged at least seven APT groups linked to the Russian government assisting Russia’s ground force, as well as at least 20 new strains of malware and nine new Wiper viruses used against Ukraine. They also report that Russian-backed hackers are conducting strategic espionage against governments, think tanks and businesses in 42 countries supporting Ukraine, with a 29% success rate.

Fig. 1. Russian Network Penetration and Cyber Espionage Activities Outside Ukraine (source: Microsoft)

Fig. 2. Coordinated Russian cyber and military operations in Ukraine (source: Microsoft)

These numbers are unprecedented. We have never witnessed a cyber war or cyber operations at this scale. The issue of attribution remains vital, yet much more urgent is guidance on the necessary and proportionate response to these attacks.

Way forward

Microsoft offers a very pragmatic solution, one deeply rooted in international law and already well established within the transatlantic framework: further advancing international cooperation by increasing the collective ability to recognise, protect against, disrupt and deter foreign cyber threats. This strategy is already being demonstrated by the European Union, whether through the Cyber Diplomacy Toolbox, advancing cyber posture or the cyber sanctions regime. Through its effective implementation in the face of advancing Russian threats Europe leads the way in modelling responsible state behaviours in cyberspace. While not at war with Russia itself, Europe is well equipped, legally and institutionally, to model responsible state behaviour in the face of cyber war at its borders. Cyberattacks targeted at Ukrainian allies in Europe and beyond require practical application of all the dogmatic discussions international lawyers from like-minded countries have had since the 2007 Estonia attacks. Applying well established norms of international law in cyberspace has always proven challenging – it requires careful consideration of case-specific circumstances and adjusting to fast-changing conditions. Europe, working together with its like-minded partners, has been able to do so efficiently and effectively, both on- and offline. Let’s hope it’s enough to win the first-ever cyber war fought at Europe’s doorstep.

Thumbnail image credits: @LucasSantos on @Unsplash