Effectively fighting cybercrime requires cooperation between different communities and stakeholders. Governments enjoy a monopoly on power when it comes to law enforcement and criminal justice, but they need the involvement of the private sector and civil society organisations to make their policies work. With the launch of a new UN process addressing cybercrime around the corner, states cannot afford to ignore the invaluable experience that non-state actors can bring to the negotiation table.

Cybercrime is a global problem that undermines the economic growth and well-being of our societies, a problem that has been growing in complexity, which renders monolithic and inward-looking responses ineffective. While various regional approaches have emerged – from Europe, Africa and Asia – there is still no universal framework to fight cybercrime.

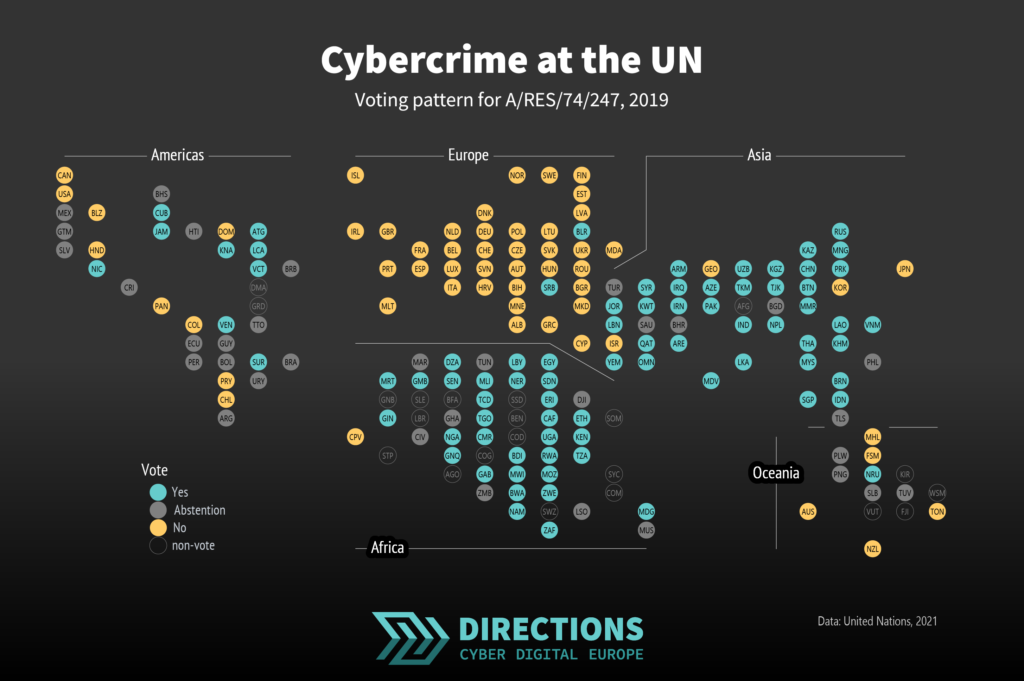

In December 2019, a resolution establishing a new open-ended ad hoc intergovernmental committee of experts was adopted at the UN to elaborate a comprehensive international convention on “countering the use of information and communications technologies for criminal purposes”. The resolution, which represents the culmination of years of Russian efforts, saw strong opposition from Western states and elicited concern from human rights organisations.

The process, which will kick off in May 2021, is inherently fraught with geopolitical tensions, given the contrasting ideas about the role of states and the competing visions of the Internet involved, in addition to the ever-increasing competition for influence over the governance of cyberspace. Uncertainties surrounding the working modalities that will be adopted in the process, the direction in which the discussion will evolve and how the new process will impact the progress achieved in the fight against cybercrime to date make anticipating the output of such an initiative difficult.

Against this background, states need to embrace civil society organisations as their allies at this critical time in the process: not only as valuable partners in shaping content but also as honest brokers between conflicting political interests.

Starting from a Position of Weakness

Before discussions about content can begin, states need to agree on the working modalities for the ad hoc committee during an organisational session. This includes appointing a chair, vice-chairs and rapporteurs; adopting the agenda; and agreeing on procedural matters, decision making processes (i.e. consensus-based versus voting-based), the venue for the sessions (i.e. Vienna versus New York) and the timeline and schedule of the work of the Committee. Importantly, in this meeting, states will also decide on the mechanisms for engagement with civil society organisations (CSOs) and non-governmental stakeholders more generally. This session has now been postponed twice and is now scheduled for May 2021.

Unlike the resolution that set up the ongoing Open-ended Working Group (OEWG) in a separate parallel UN process to discuss responsible state behaviour in cyberspace, the cybercrime resolution does not mention the role of non-state actors. Although there is no guarantee that including them in the text is sufficient to secure non-state participation – as evidenced by the meetings of the OEWG, where the participation of non-state actors with no special consultative status with the UN (known as ECOSOC status) has been blocked by some states on a number of occasions – it does help in pushing for a more active role. The working modalities for the Committee proposed by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) reference the contributions of intergovernmental organisations, non-governmental organisations, civil society and the private sector – building on the practice established by the Ad Hoc Committee on the Elaboration of a Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC) and the Ad Hoc Committee for the Negotiation of a Convention against Corruption (UNCAC). However, states can decide against such contributions.

As things stand, the foundation for civil society participation is still weak.

In a joint comment, Australia, Canada, Chile, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, the United Kingdom and the United States stressed that “given the multi-stakeholder nature of cyberspace, any new convention elaborated without taking into account the views of all stakeholders, including civil society and the private sector, would be incomplete”. What is worrying, however, is the growing push by countries such as Egypt to distinguish between engagement with the private sector and engagement with civil society. They are also of the view that the “participation of those [CSOs] that enjoy consultative status with ECOSOC, via the standard mechanisms, should be sufficient”, which would result in the exclusion of considerable expertise.

An Ally, Not an Enemy

The cybercrime ad hoc committee will work towards a comprehensive international convention on countering the use of information and communications technologies (ICTs) for criminal purposes – an objective that goes far beyond fighting cybercrime in scope. Such a broad scope implies that reaching an agreement on the goals and definitions of the convention will be very difficult to achieve. The absence of a universally accepted definition of cybercrime already creates obstacles to cooperation between states. What is certain, however, is that fighting cybercrime is a shared responsibility requiring governments, experts, civil society organisations, the private sector and citizens to act collectively at the domestic and international level.

Civil society organisations, in particular, can be important allies in ensuring that decisions are driven by facts and research rather than politics. There is a common misconception that CSOs can be instrumentalised to take sides in political debates. While this might sometimes be the case, CSOs primarily seek to ensure that the fight against cybercrime is conducted with respect for human rights and that its responses are guided by the principles of legality, proportionality, necessity and respect for human rights.

In this respect, CSOs have numerous functions worth emphasising:

- Brokering and overcoming stalemates: UN conversations around ICT policies have been consistently reflective of the inherent geopolitical differences between the major cyber powers. The conversation around cybercrime is no different, as the tensions around the organisational meeting have shown. A well-informed and experienced civil society can help keep the negotiations focused on the subject matter and help provide fresh perspectives that may be crucial in overcoming inevitable deadlocks. The role of CSOs as honest brokers is even more important in such a highly politicised context.

- Ensuring accountability and protecting human rights: CSOs (a) support the development of cybercrime policies that are human-centric, (b) raise the alarm on potential human rights abuses when policies are being made, and (c) monitor for accountability in policy implementation. For instance,in the ongoing negotiations for the second additional protocol of the Budapest Convention (the Council of Europe Convention on Cybercrime), CSOs played a key role in flagging human rights concerns and in pushing the drafters to reconsider some of their provisions.

- Providing knowledge and expertise: CSOs have a wealth of technical and substantive expertise that can be used to frame the problem and support the development of effective policies. This is true in particular for developing countries, which often lack resources – human, technical, financial or a combination. In that sense, CSOs play an important role as allies that can put policymaking into different contexts, ensuring that policies are grounded in the realities of different countries and regions.

- Promoting policy coherence and transparency: CSOs can support international negotiations by establishing linkages with other cyber/digital areas,such as cybersecurity, and the efforts that are ongoing in other forums, especially within the UN. CSOs also help to incorporate other development priorities, such as gender equality and the Sustainable Development Goals, into cybercrime policymaking. By ensuring policy coherence, CSOs help minimise the risk of states forum shopping in search of their preferred outcome.

- Legitimacy and capacity building: As highlighted by a number of states, any convention that needs to be ratified by governments but that CSOs and other non-government actors haven’t played a role in shaping will be incomplete. CSOs play a key role at the national level, in particular in building trust around international instruments and in helping operationalise those agreements. CSOs don’t just support the development of effective and inclusive policy development through negotiation, they also assist with their implementation and ultimately help to create a more resilient cyber ecosystem.

- Avoiding duplication: The involvement of civil society can also serve to reduce a significant risk – the temptation to reinvent the wheel to the detriment of progress already achieved, both in terms of policy and operational cooperation. To that end, it is critical to structure the international community’s efforts around addressing already-identified gaps and challenges through long-term technical assistance and capacity-building. CSOs can help with that.

The UN Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice (CCPCJ) has for years been the main venue for the discussion of cybercrime in the UN context. It has conducted regular engagement with civil society organisations through the Alliance of NGOs on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice, amongst others. There is a risk, therefore, that this momentum might be lost or insufficiently reflected in the new process.

Ensuring sustainable outcomes

As states contemplate how they want to engage in the cybercrime ad hoc committee, cybercriminals have been for years honing their expertise and getting better at inflicting damage. The need for states to pool their resources and efforts to address this challenge has never been greater. Civil society is an important ally in this effort.

In order to increase their chances of success, states need to ensure the broadest possible access to the process for civil society organisations and the private sector. Attempts to establish differentiated modes of participation for the private sector and CSOs would set a dangerous precedent. The private sector indeed plays an important role in the field of ICTs but they are ultimately bound by the laws adopted by states and accountable to their shareholders. As a consequence, civil society organisations are uniquely placed to ensure that cybercrime policies are fit for purpose; protect civil liberties, human rights and innovation online; and enable ICTs to play their role as catalysts for socio-economic development.

Thumbnail image: Credits to Ryoji Iwata on Unsplash