Disinformation and foreign influence operations are no longer just threatening the political, economic and social foundations of our societies. As the spread of COVID-19-related disinformation has shown, they can now also cause direct harm and cost human lives. As global efforts to counter disinformation grow, it’s time to seriously discuss possible consequences for those behind it.

The ongoing global pandemic has once again shone a spotlight on the problem of disinformation. On the heels of its effort to counter foreign influence operations during the elections, the European Union is now targeting disinformation campaigns related to COVID-19. The issue is different, but the assumed villains are the same: Russia and China. In addition, new actors such as Iran and Turkey are slowly entering the stage. According to the new Joint Communication presented by the European Union in early June, foreign actors are “engaged in targeted influence operations and disinformation campaigns” in the EU, its neighbourhood and globally. Their aim is straightforward: “to undermine democratic debate and exacerbate social polarisation, and improve their own image in the COVID-19 context”.

The remedies proposed in the document combine self-help mechanisms, policies aimed at online platforms and increased support for fact-checkers and researchers. The first category includes, for example, improving coordination on disinformation within existing structures and sharing best practices. Policy interventions aimed at improving the transparency of online platforms could include, for example, monthly reports on policies and actions addressing COVID-19-related disinformation. Finally, fact-checkers and researchers can be supported by broadening and intensifying their cooperation with platforms. Research shows the effectiveness of these institutions is limited, but the Communication is still a commendable effort to respond to a serious problem.

The sad truth, however, is that all previous efforts to curb disinformation have caused very little change in state behaviour. It is hard to see why it would be different this time around. The biggest weakness of the proposed measures is their failure to impose consequences on or hold accountable states who actively engage in disinformation and influence operations against the EU, its member states or allies. These are not easy tasks, as Dennis Broeders explained: political unwillingness to call out information operations as violations of international law and diplomatic reservations about discussing information security limit the available political and legal responses. So, what else can be done?

Illegality of Disinformation

The underlying assumption behind existing responses to disinformation is that, while it may be politically and morally unacceptable, most of it is not illegal or unlawful. Any response is also expected to carefully balance respect for fundamental rights – in particular freedom of expression – and democratic values. This respect for law and fundamental freedoms is generally assumed to constrain responses to disinformation – but what if it could liberate them?

Can responses to disinformation leverage defence of the rules-based international order and fundamental freedoms as powerful tools rather than treat them as limitations?

This is not an entirely new idea. Ahead of the European elections in 2019, the European Union adopted political guidelines for securing free and fair elections. The document established the freedom to receive and impart information and ideas without interference from public authorities as a precondition for legitimacy and fairness of electoral processes. As such, any interference with this freedom – whether domestic or external – is a clear violation of fundamental freedoms. Aside from a few (debatable) examples, a similar level of imagination has been missing from the response to COVID-19-related disinformation.

To be fair, the document on the table does include three approaches to regulating and imposing consequences for disinformation-related actions:

- Disinformation as a violation of consumer protection laws: Consumer fraud is patently illegal and can be concretely handled by consumer protection authorities and online platforms. For instance, in March the US Department of Justice issued a restraining order against a site selling a bogus coronavirus vaccine and engaging in a wire fraud scheme.

- Disinformation as a violation of cybercrime laws: COVID-19-related hacking and phishing operations based on disinformation techniques are also common and can be responded to by law enforcement authorities. Banks in Poland reported SMS messages urging recipients to log in to their online banking accounts to avoid “mandatory” contributions to the COVID-19 effort, or asking for a fee to register for vaccination. Google reported that, during one week, it saw 18 million malware and phishing emails and 240 million spam messages related to COVID-19 every day.

- Disinformation as violation of a contract: Social media is clearly one of the main channels for disinformation. Researchers from the Carnegie Mellon University analysed about 200 million tweets discussing COVID-19 since January and concluded that about 45 percent of the involved Twitter accounts were likely automated. Violations of the site’s terms of service then becomes the main legal mechanism giving the social media platform sanctioning powers. This is why cooperation with social media platforms on content control and transparency measures is a key pillar in the fight against disinformation. Certain Domain Name Registration (DNS) companies have also taken steps to effectively block incoming COVID-19 related domain registrations and to cooperate better under the umbrella of the DNS Abuse Framework.

These mechanisms, however, focus primarily on actions by individuals and fail to address the problem of disinformation and influence operations orchestrated by states. They might increase the cost of such activities, but ultimately are unlikely to deter states that already engage in such malicious operations.

Disinformation and State Obligations

States do not operate in a legal or political vacuum. Many existing international norms and laws make COVID-19 disinformation operations by states illegal:

- Disinformation as a violation of the right to health: Disinformation campaigns related to COVID-19 have included dangerous hoaxes and misleading healthcare information. Such content can directly endanger lives and severely undermine efforts to contain the pandemic, resulting in further deaths. COVID-19-related disinformation campaigns orchestrated by states could thus be considered to violate the right to health enumerated in international agreements such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (article 25); the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (article 12); and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (article 25).

- Disinformation as a violation of freedom of expression: The EU is committed to fighting disinformation while also protecting freedom of expression. This right can be used as a double-edged sword. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (article 19) states clearly that the fundamental right of freedom of expression encompasses the freedom “to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers”. State-sponsored disinformation and influence operations could be interpreted as violating individuals’ right to receive information: they aim to make it more difficult for individuals to find, trust or verify correct information, though they accomplish this not through direct censorship but by flooding channels with spurious disinformation. This is, of course, a complex issue, and has been addressed by the courts, e.g. in the Delfi AS v Estonia case.

- Disinformation as a violation of good relations among the states and principle of non-intervention: The non-intervention rule (article 2.4 of the UN Charter) is a principle of international law that restricts the ability of outside nations to interfere with the internal affairs of another nation. The exact scope of the non-intervention principle is debated, and Russia and China often use it to criticise Western engagement in their territory and in other parts of the world. Regardless, disinformation goes against the spirit of the UN Charter, which calls on the states to abstain altogether from actions that might threaten international peace and security.

That being said, how can these theoretical approaches be translated to practice? Can they be used to impose consequences for spreading disinformation?

From Words to Actions

When announcing the package of proposed measures, the EU High Representative Josep Borell could not have been clearer: “disinformation in times of the coronavirus can kill”. Such a clear statement creates a legitimate expectation that something must – and will – be done. But, so far, the EU’s diplomatic response has been reactive in nature. The regular reports published by the European External Action Service call out, name and shame, or raise awareness about disinformation and interference operations by third countries. Individuals engaged in disinformation campaigns can also be punished through public naming – the practice known as doxing.

Acknowledging how disinformation violates concrete norms of international law can be empowering. It creates a number of opportunities for the European Union to adopt a more proactive posture on the global stage.

1. Make a better use of the Cyber Diplomacy Toolbox: The main purpose of EU cyber diplomacy is to reduce the risk of conflict, strengthen accountability and promote responsible state behaviour in cyberspace, with the ultimate aim of defending the open, free, safe and secure nature of cyberspace. Disinformation and information operations violate at least a couple of these principles and, as such, should be targets of the EU’s cyber diplomacy efforts.

- In line with its commitment to multilateralism and rules-based order, and building on its experience in fighting disinformation within its borders, the EU should support and spearhead a global effort aimed at clarifying and promoting the application of existing international law and norms to fight disinformation globally. Such an effort could built on the Cross-Regional Statement on “Infodemic” in the Context of COVID-19, which calls for “everybody to immediately cease spreading misinformation” and to observe UN recommendations on this matter.

- Make a better use of already-existing tools – including international agreements, political dialogues, capacity building and technical assistance – to support other countries in creating appropriate institutional and regulatory conditions to fight disinformation. In cases where disinformation and influence operations are linked to unlawful access to network systems, the EU – like the United States – could resort to potentially more impactful instruments, such as cyber sanctions (as explained by Thomas Reinhold in the case of Germany).

2. Turn human rights action into a powerful tool: Existing international law can serve as a powerful weapon to fight disinformation and influence operations. The EU Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy presented in March 2020 could become a useful mechanism to promote the existing rules. It could do so by promoting the principles of open, safe, affordable and non-discriminatory Internet access, which would in turn strengthen the global information ecosystem (including civil society and independent media). Fighting disinformation and influence operations could become a joint initiative of the EU Special Representative for Human Rights and the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression or other international organisations. In addition, the EU’s human rights sanctions regime, currently in progress, could specifically include in its scope violations of human rights online, filling in the existing gap.

Disinformation and influence operations are sensitive, complex topics. But we can no longer pretend that the problem is not there. Europe needs to re-own the global conversation about disinformation, as a counterweight to the worldviews promoted by China and Russia. A creative European (cyber)diplomacy may just provide the right answers.

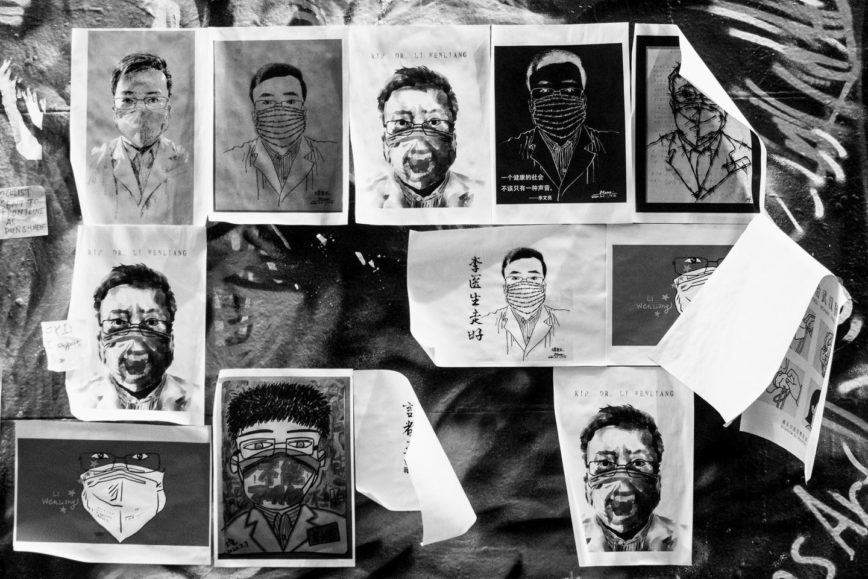

Featured image: credits to Adli Wahid