The establishment of the UN Ad Hoc Committee to Elaborate a Comprehensive International Convention on Countering the Use of Information and Communications Technologies for Criminal Purposes was the result of a highly politicised approach by certain countries regarding international cooperation to fight cybercrime. Even though the Ad Hoc Committee has not even started working on substance, the disagreements over the modalities and principles that should guide the negotiation process indicate a large polarisation on cybercrime issues. Tracking votes cast by individual countries at the United Nations may give us at least partial answers concerning the main drivers of cooperation and conflict in this domain.

Tracking voting patterns at the United Nations is a common way to monitor the level of convergence among countries, to identify patterns or potentially map the evolution in the positions taken by a particular country on a given issue. This data brief analyses four different votes at the United Nations as well as country positions towards the Budapest Convention. We look at four specific votes in order to assess the global convergence with the positions presented by the European Union:

- Resolution 74/247 establishing an open-ended ad hoc intergovernmental committee of experts, representative of all regions, to elaborate a comprehensive international convention on countering the use of information and communications technologies for criminal purposes.

- The Brazilian amendment (L90) which set the decision-making threshold at a 2/3 majority of representatives present (closer to the consensus decision making favoured by the EU) rather than the simple majority (favoured by Russia).

- The UK amendment (L92) which decreased the ability of states to block external participants (promoting more multistakeholder engagement) by ensuring that any objection must be agreed by the ad hoc committee.

- The Dominican Republic amendment (L33) concerning the postponement of the first substantive meeting due to Covid-19 concerns and to allow for inclusivity, openness, and transparency of the process.

The World Divided

Analysis of the votes reveals a rather divided picture of the world: 37 countries showing divergent or very divergent views when compared to the EU’s stance on cybercrime. Most of them are in Africa or Asia. While continuing dialogue is important, the EU and like-minded countries need to focus their attention on an equally large group of countries (74) who can be seen as “swing votes” on cybercrime issues.

The World in Transition

The rather positive assessment of the static image presented above does, however, becomes less optimistic when looking at the evolution of voting patterns in individual regions. The number of abstentions or no-votes in Africa and Asia is particularly noteworthy. At the same time, out of the 79 countries who supported the Russian proposal for establishment of the Ad Hoc Committee in 2019, 38 countries (or 48%) have changed their position by abstaining or not voting at all on the decision(s) regarding the modalities of the Ad Hoc Committee on Cybercrime.

Regional Disparities

No other region in the world shows a similar level of within-region coherence than Europe. However, there are significant disparities between the EU and the rest of the world. The voting patterns on the working modalities for the Ad Hoc Committee demonstrate growing convergence between the EU and other regions, in particular Latin America. Still, many countries in Africa and Asia seem to be beyond the EU’s reach.

Countries to Watch

The comparison of the UN voting patterns with the positions adopted towards the Budapest Convention offer interesting insights. Senegal stands out as a country that has consistently voted contrary to the EU, despite having joined the Budapest Convention and receiving significant EU support through the GLACY+ project. Sri Lanka demonstrates a similarly worrying pattern even though it has abstained in the vote on L33. In some cases, Burkina Faso and Mauritius – two other signatories – have changed their position from neutral to vote contrary to the EU. Until the most recent vote on L33, Nigeria was the only country whose votes have evolved towards convergence with the EU position.

Regarding the working modalities, the assessment of the positions taken by certain countries is not straightforward. Nine countries – notably India and Uganda – supported modalities for strengthening civil society participation in the work of the Ad Hoc Committee but were only prepared to accept decision-making on a majoritarian basis (50+1). On the other hand, 15 countries – notably Morocco, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Turkey – supported the two-thirds majority vote proposal (L90) but did not support the UK amendment on multistakeholder participation (L92).

Meaningful Engagement

The engagement on cyber diplomacy by the EU and like-minded countries has resulted in quite a significant shift towards alignment with the EU positions. Although no meaningful change in the positions of most countries is recorded, there are only two states who have wholly departed from the alignment with the EU: Cape Verde and the Marshall Islands. At this point in time, there is no country in the world that has evolved to completely align its positions with the EU.

COVID Diplomacy

The work of the Ad Hoc Committee started in the very difficult context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, several discussions took place concerning the first substantive session which was initially scheduled for January and postponed again. While countries like Russia would like work on the Convention to start as soon as possible, other countries – including the EU – are pushing for delaying work until conditions are favourable enough to allow for in-person meetings with the participation of experts from all countries. Therefore, behind the concerns about the health of delegates lies also a more politically driven expectation, that participation of experts in cybercrime will increase the chances of ensuring that the rules and principles shared by the EU are also embraced by the rest of the world.

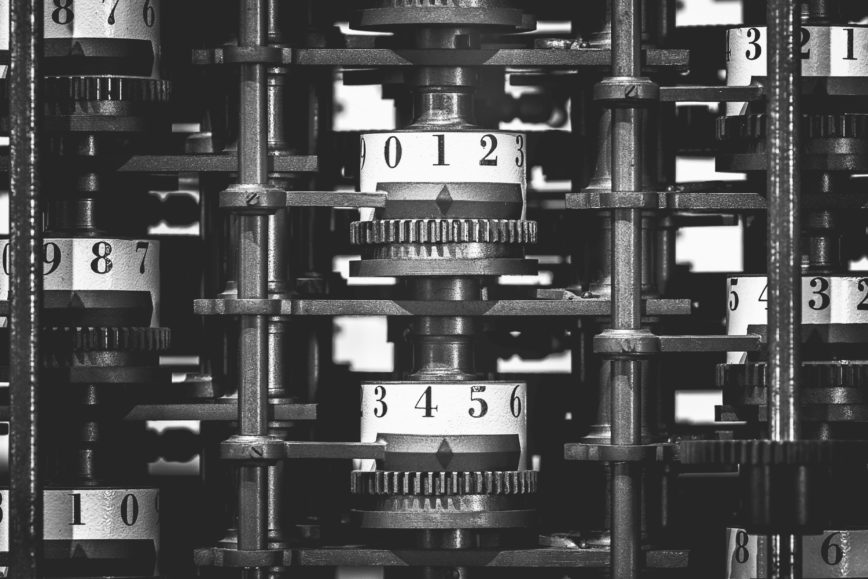

Thumbnail Image credits: @Mint_Images on @EnvatoElements