The spring of 2021 brought two landmark international cybersecurity events: all UN member states lined up behind the final report of the Open-ended Working Group, and the UN GGE of 25 government experts was able to produce a consensus report. These breakthroughs mark the beginning of a more nuanced dialogue and an era in which, to break truly common ground on the question of international peace and security in the context of ICTs, concessions are expected from all leading actors.

OEWG: Painting the Bigger Picture

The Open-ended Working Group on developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security (OEWG) has fundamentally changed the international cybersecurity discourse. Although some states objected early on to all-inclusive participation and contributions from civil society and other non-state actors, over the last year and a half the dialogue has become more transparent and inclusive, and therefore more accountable. The global pandemic has served as a catalyst to acknowledgement of cybersecurity not just as a peace and security issue but as a cross-cutting aspect of international development and prosperity.

Especially welcome is the acknowledgement, first made by the OEWG, that international cybersecurity, even with an emphasis on peace and security, is too broad a theme to be successfully resolved in the First Committee. Further, the OEWG’s process has been shaped by the UN Charter – and not just by its letter, but by its ideals: sustainable peace, development and humankind. The OEWG has ensured that, for the foreseeable future, the UN remains the leading platform for addressing issues of international cybersecurity. While there are no guarantees of success in this turn towards multilateralism, the OEWG report underscores the aims cyber diplomacy seeks to achieve and serve: economic growth, sustainable development, human rights and fundamental freedoms. The OEWG has also connected cybersecurity and development, underscoring how important it is that any consensus or commitments reflect the concerns of the whole international community, not only its most-connected members.

Together with its sister process, the Group of Governmental Experts on Advancing responsible State behaviour in cyberspace in the context of international security (UN GGE), the OEWG has cemented the framework in which responsible state behaviour will be discussed under the UN auspices: international law, voluntary norms and confidence-building measures as the main instruments for achieving international cybersecurity. Compared to earlier stages of the international dialogue, more emphasis has been added on measures to be taken at the national level – both to implement what has been negotiated and agreed to in the UN and to further boost national contributions to an open, secure, stable, accessible and peaceful cyberspace, for instance by national legislation.

Despite welcoming civil society, industry and other non-state actors to the dialogue, the texts of both the OEWG and UN GGE hardly promise equal-level engagement between governments and non-government actors. International cybersecurity decisions remain within government purview and the words “as appropriate” and “in their respective roles” suggest that individual governments under their respective national regimes will decide whether civil society and industry are involved in actual decision-making and implementation. The opportunity to engage has not offered any civil society group or industrial player a driver’s seat in the discourse – and it seems unlikely that this will change in the near future. Accordingly, differences of opinion about how to best implement the framework of responsible state behaviour persist between different groups.

GGE: Thorny Issues Remain

The GGE report hints at some persistent differences. For instance, the 2021 UN GGE report reveals no final settlement on lex specialis: experts have simply noted the possibility of additional binding obligations in the future. The resolution establishing the next OEWG 2021-2025 puts heavy emphasis on further development of the rules, norms and principles of responsible behaviour of states and on, if necessary, introducing changes to them or elaborating additional rules of behaviour. In this context, the report also does not add substance to the existing sub-optimal language in the 2015 UN GGE report (paragraphs 16 and 19). The clarification that International Humanitarian Law (IHL) only applies in situations of armed conflict reads both like a nod to those who have emphasised the nexus between IHL and militarisation of cyberspace and like another blank round from those who want to persuade the spectators that IHL adequately addresses the use of ICTs in cyber operations.

Both groups have made substantive progress on the norms of responsible state behaviour, as was to be expected given the progress that was made, albeit never adopted, by the 2016-2017 UN GGE. In particular, the 2021 UN GGE report offers a thorough commentary on how the 2015 recommendations are to be implemented. Reports of implementation and exchanges of relevant practices will appear in the coming months and years. Several states have already issued their preferred implementation guidelines and processes have been initiated to promote a uniform understanding of what was agreed to in the UN processes. Whether less capable countries and actors with divergent views will follow suit is one of the challenges for the proposed Programme of Action.

The Elephant in the Room

On international law, the 2021 reports may read as having little to say. The progress, however, is in quality rather than quantity. One anticipated development is both reports’ recognition that anything in them is without prejudice to existing international law. Also, both the OEWG and UN GGE significantly expand the discussion of the applicability of international law by underscoring the obligation and principle of peaceful settlement of international disputes – something that has not received attention in earlier processes. International tensions now have a cyber component due in part to insufficient and emphasis on and attention paid to peaceful settlement of disputes. Both the OEWG and UN GGE have expressed concern about peacetime cyber operations, development of military cyber capabilities and the increasingly likely use of ICTs in future conflicts – issues which are not directly discussed but on which clarity is needed. The two reports only begin to address the complex obligation of peaceful settlement. However, even a first call to urge states to make better use of this obligation opens possibilities for discussing disputes that states have in or around cyberspace and optimal ways to resolve them.

Apart from this promising addition, how international law applies to state use of ICTs remains a divisive issue. Russia has not backed away from its positions stated early in the process and, together with China and a few other countries, restated them in the proposal for an international code of conduct for information security. The mostly like-minded campaign of statements on the application of international law (IL) is still in an early phase and may lead to further difficulties – for example, how to explain or resolve the differences that the otherwise aligned countries have in their approaches to IL. Due to its operational emphasis, the like-minded advocacy of the Tallinn Manual on the IL applicable to cyber operations is also unlikely to convince all states.

Three major challenges lie ahead. Although states have started declaring their views on the application of IL in cyberspace, there is no international consensus on several fundamental questions. Major powers have acute and serious interests in keeping their options open, and frame discussions about international law to serve their own interests. Convincing other states of “our” stances will require acknowledgment of their respective realities and interests.

Second, many debates are still ahead of us. Like the new theme of peaceful settlement, many questions of international law have not been opened, or even raised, in the process. Still ahead is a wider international discussion of questions such as whether and how low-intensity cyber operations in peacetime violate national sovereignty or the prohibition of intervention; whether they are consistent with the principles and obligations of friendly relations, good faith and peaceful settlement; whether due diligence is an overarching binding obligation or applies through more concrete modalities; or whether cyber espionage is “not illegal” under international law.

Third, despite the effort to draw a clear line between the issues of international law and non-binding norms, international law on state uses of ICTs is in the making. The question to be asked in conjunction with the norms agenda is if anything about it is still voluntary and non-binding – or if we’re factually moving towards new binding obligations. The like-minded have lined up behind an agenda of norms enforcement, i.e. imposing consequences on those who deviate from the recommendations (and now, potentially, their suggested implementation). However, for those states that have advocated the need for additional norms, rules and principles, the rhetoric of voluntary and non-binding does not change the fact that the world is discussing new rules of the road (or the game). Consequently, the states that want to avoid discussions of international law may also want to avoid discussions of further norms, as these open the door to inquiries and propositions about the inadequacy of the current international consensus. All in all, more tensions are likely to mount in the norms department.

What’s Next?

The fact that both the OEWG and the UN GGE have resulted in consensus reports suggests a somewhat satisfactory equilibrium has been established between the major powers. Despite their otherwise very structured, eloquent and coherent language, both OEWG and UN GGE reports are abstract enough to allow both sides to build on what they have achieved so far. Therefore, 2021 is not a reset, it is a continuation, as both reports many times iterate.

As of 2021, everybody wins – civil society and industry have gained access to the dialogue. The US got the UN GGE. Russia got the OEWG. The like-minded have incepted the idea of a Programme of Action, perhaps in hopes of sustaining some of the status quo. Pessimists received not one but two reports. Above all else, the 2021 outcome of two reports is a victory of diplomacy as a process of seeking and finding common ground where there seems none.

In the OEWG’s transparency and “democracy” lie the potential for further progress. Even if reluctantly, the major powers are forced to discuss concerns of the rest of the world. In this context, 2021 signifies the importance of cyber diplomacy, not just between the major powers, but between all countries, as a skill and as an investment, and pushing all to acknowledge their national cybersecurity situation and the ways in which it could be aided by international measures.

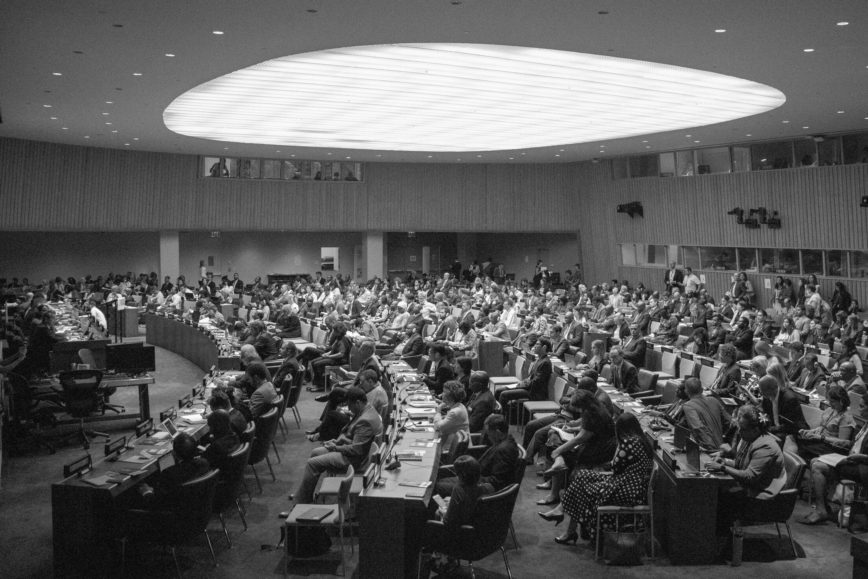

Thumbnail Image: Credits to Matthew TenBruggencate from Unsplash.